If you happened to be a young person in 1965 it was hard to know

where to look next as the frivolity of sport and song jostled with

events profound enough to reshape the world. The year had barely begun

when Malcolm X was assassinated while preparing to address a meeting in

New York. The Beatles picked up their MBEs and played Shea Stadium.

Lyndon Johnson sent the first ground troops to Vietnam. PJ Proby’s

velvet trousers split on stage in Croydon. The Kray brothers were

remanded and the Moors murderers charged. Liverpool won the FA Cup for

the first time and Stanley Matthews played his last match, aged 50.

More? Three Rolling Stones were fined a fiver each for urinating in a petrol station forecourt in Essex on the way home from a show. India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir while mods and rockers fought on the beach in Brighton. Jim Clark became the first non-American driver to win the Indy 500. David Bailey married Catherine Deneuve. Incitement to racial hatred was banned in the UK. The model Jean Shrimpton scandalised Australian society by turning up for the Melbourne Cup in a dress with a hem three inches above the knee. Bob Dylan went electric and the year’s endless parade of hits included Like a Rolling Stone, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, Stop! In the Name of Love, My Generation, Help, In the Midnight Hour, California Girls, I Got You Babe, Mr Tambourine Man, The Tracks of My Tears and You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’.

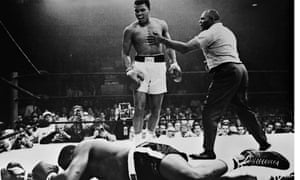

And 50 years ago this Monday, in the midst of that social, political and cultural maelstrom, the former Cassius Clay, fighting for the first time as Muhammad Ali, took one minute and 44 seconds to demolish Sonny Liston’s attempt to recapture his world heavyweight title.

On the night of 25 May, 1965 in Lewiston, Maine, the history of boxing and much else besides was changed by a punch that few, even those at ringside, actually saw. The defeat effectively finished the career of Liston, who had once seemed invulnerable, and it did as much as any other single incident to create the imperishable legend of Ali.

In a battle between the Nation of Islam and the mobsters, who controlled a large part of the boxing world, both sides won. Elijah Muhammad and his disciples gained the publicity that accrued from a freshly crowned world heavyweight champion making a successful first defence of the title under his new Muslim name. The mobsters took their profit on large sums of cash staked at favourable odds when Liston was sent to the canvas by what appeared to be an innocuous right-hander.

Endless replays of the minimal available footage have failed to solve the mystery of what became known as “the phantom punch”. Whatever it was, it caused Liston – who had come into the ring looking like his usual 215lb package of muscle and malign intentions – to fall on his back, roll over on to his front, try to rise, fail, then try again and briefly succeed before the confused referee, the former champion Jersey Joe Walcott, belatedly indicated, after consulting the timekeeper, that the challenger had not made the count of 10.

In Liston’s earlier years he had scared people and broken a few heads on behalf of John Vitale, a St Louis mob boss to whom he also acted as a chauffeur. During his rise towards international fame he was managed by Frank “Blinky” Palermo, a Philadelphia-based associate of the notorious Frankie Carbo, who – among other distinctions – had organised the murder of Bugsy Siegel in 1947. The pair were later convicted of conspiracy and extortion in connection with their boxing activities and Palermo served seven years of a 25-year prison sentence before dying, aged 91, in 1996. He left behind a celebrated quote: “The trouble with boxing today is that legitimate businessmen are horning in on our game.”

Palermo was on the outside on 25 February, 1964, when Ali, fighting for the last time as Cassius Clay, had taken Liston’s title in a Miami ring. There were rumours about the integrity of that fight, too, particularly when so much late money went on the younger man that the odds tumbled from what had seemed a realistic 5-1 to something approaching 2-1 by the time the fighters entered the ring. The apparently undamaged champion failed to answer the bell for the start of the seventh round, claiming that his left arm had gone numb.

The author Nick Tosches, in his great biography The Devil and Sonny Liston (later retitled Night Train), leaves little doubt that both fights were fixed. Not that Ali would have necessarily been a party to the arrangement. As Tosches points out, the mob’s technique was to make the deal only with the designated loser. The winner might suspect that something had been amiss, but he would never know for sure.

After experiencing trouble in finding a venue for the rematch, the promoters settled on St Dominic’s Hall in out-of-the-way Lewiston. Several hundred empty seats were left after the 2,434 ticket-holders turned up, making it a record low attendance for a heavyweight title fight in the modern era. The big money would come from closed-circuit transmission to cinemas across America.

The popular crooner Robert Goulet sang The Star Spangled Banner before Ali entered the ring to the sound of booing. His youthful brashness had earned disapproval from white and black alike, but this was a reaction to his decision to embrace Islam, announced the morning after the first fight. His opponent, by contrast, was greeted with cheers: however intimidating he may have seemed, he represented a more familiar and even comforting archetype. “Sonny Liston – very popular with the folks here in Lewiston, Maine, no kidding about that,” the US commentator said, with a note of surprise in his voice.

Circling the ring in a clockwise direction as he shuffled out of Liston’s reach, Ali never looked as though he were about to unleash a thunderbolt. The nature of the decisive blow merely added to the growing mystique of a boxer who seemed to have found a whole new way to fight.

He defended his title eight times in the next 21 months before his opposition to the Vietnam war led him to be stripped of his title. He would win it back, having forfeited a big stretch of his prime. But to a year of mingled horrors and wonders he had added 104 seconds of action over which heads are still scratched.

More? Three Rolling Stones were fined a fiver each for urinating in a petrol station forecourt in Essex on the way home from a show. India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir while mods and rockers fought on the beach in Brighton. Jim Clark became the first non-American driver to win the Indy 500. David Bailey married Catherine Deneuve. Incitement to racial hatred was banned in the UK. The model Jean Shrimpton scandalised Australian society by turning up for the Melbourne Cup in a dress with a hem three inches above the knee. Bob Dylan went electric and the year’s endless parade of hits included Like a Rolling Stone, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, Stop! In the Name of Love, My Generation, Help, In the Midnight Hour, California Girls, I Got You Babe, Mr Tambourine Man, The Tracks of My Tears and You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’.

And 50 years ago this Monday, in the midst of that social, political and cultural maelstrom, the former Cassius Clay, fighting for the first time as Muhammad Ali, took one minute and 44 seconds to demolish Sonny Liston’s attempt to recapture his world heavyweight title.

On the night of 25 May, 1965 in Lewiston, Maine, the history of boxing and much else besides was changed by a punch that few, even those at ringside, actually saw. The defeat effectively finished the career of Liston, who had once seemed invulnerable, and it did as much as any other single incident to create the imperishable legend of Ali.

In a battle between the Nation of Islam and the mobsters, who controlled a large part of the boxing world, both sides won. Elijah Muhammad and his disciples gained the publicity that accrued from a freshly crowned world heavyweight champion making a successful first defence of the title under his new Muslim name. The mobsters took their profit on large sums of cash staked at favourable odds when Liston was sent to the canvas by what appeared to be an innocuous right-hander.

Endless replays of the minimal available footage have failed to solve the mystery of what became known as “the phantom punch”. Whatever it was, it caused Liston – who had come into the ring looking like his usual 215lb package of muscle and malign intentions – to fall on his back, roll over on to his front, try to rise, fail, then try again and briefly succeed before the confused referee, the former champion Jersey Joe Walcott, belatedly indicated, after consulting the timekeeper, that the challenger had not made the count of 10.

In Liston’s earlier years he had scared people and broken a few heads on behalf of John Vitale, a St Louis mob boss to whom he also acted as a chauffeur. During his rise towards international fame he was managed by Frank “Blinky” Palermo, a Philadelphia-based associate of the notorious Frankie Carbo, who – among other distinctions – had organised the murder of Bugsy Siegel in 1947. The pair were later convicted of conspiracy and extortion in connection with their boxing activities and Palermo served seven years of a 25-year prison sentence before dying, aged 91, in 1996. He left behind a celebrated quote: “The trouble with boxing today is that legitimate businessmen are horning in on our game.”

Palermo was on the outside on 25 February, 1964, when Ali, fighting for the last time as Cassius Clay, had taken Liston’s title in a Miami ring. There were rumours about the integrity of that fight, too, particularly when so much late money went on the younger man that the odds tumbled from what had seemed a realistic 5-1 to something approaching 2-1 by the time the fighters entered the ring. The apparently undamaged champion failed to answer the bell for the start of the seventh round, claiming that his left arm had gone numb.

The author Nick Tosches, in his great biography The Devil and Sonny Liston (later retitled Night Train), leaves little doubt that both fights were fixed. Not that Ali would have necessarily been a party to the arrangement. As Tosches points out, the mob’s technique was to make the deal only with the designated loser. The winner might suspect that something had been amiss, but he would never know for sure.

After experiencing trouble in finding a venue for the rematch, the promoters settled on St Dominic’s Hall in out-of-the-way Lewiston. Several hundred empty seats were left after the 2,434 ticket-holders turned up, making it a record low attendance for a heavyweight title fight in the modern era. The big money would come from closed-circuit transmission to cinemas across America.

The popular crooner Robert Goulet sang The Star Spangled Banner before Ali entered the ring to the sound of booing. His youthful brashness had earned disapproval from white and black alike, but this was a reaction to his decision to embrace Islam, announced the morning after the first fight. His opponent, by contrast, was greeted with cheers: however intimidating he may have seemed, he represented a more familiar and even comforting archetype. “Sonny Liston – very popular with the folks here in Lewiston, Maine, no kidding about that,” the US commentator said, with a note of surprise in his voice.

Circling the ring in a clockwise direction as he shuffled out of Liston’s reach, Ali never looked as though he were about to unleash a thunderbolt. The nature of the decisive blow merely added to the growing mystique of a boxer who seemed to have found a whole new way to fight.

He defended his title eight times in the next 21 months before his opposition to the Vietnam war led him to be stripped of his title. He would win it back, having forfeited a big stretch of his prime. But to a year of mingled horrors and wonders he had added 104 seconds of action over which heads are still scratched.

0 comments :

Post a Comment